Update September 2017 - consultation on scheme open until 17 November 2017 bit.ly/2guM5Ag

However the review is also timely in providing an opportunity - overdue at that - to review the value for money of the social benefits that the scheme provides. Leaving to one side wider issues of taxation and spending, the very considerable concessionary travel budget is currently poorly targeted at people who need it.

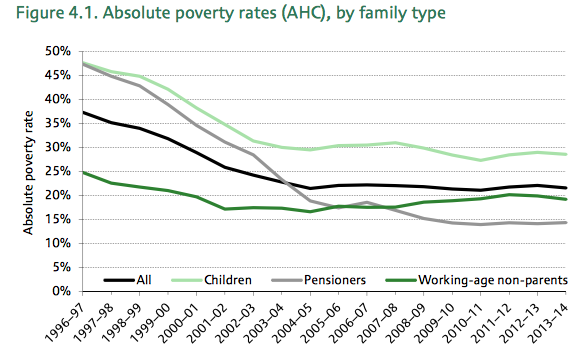

The increasing affluence of older people is not a new phenomenon; over the past thirty years, the old link between poverty and old age - once a justifiable basis for age-related travel concessions and other social security benefits - has not just reduced, but has disappeared entirely. Older people (i.e. those who qualify for free concessionary travel on age grounds) are now one of the least-poor age groups in the UK as the chart below from the Institute for Fiscal Studies shows (5).

Of course, concessionary travel is not aimed only at older people; the scheme has long been been open to blind and disabled people, and this aspect of the scheme seems well justified. However, it is important to acknowledge too that there is a major gap in the scheme. Thousands of disabled people who can’t use the bus - for example because it isn’t accessible or the bus stop is too far away - derive no benefit at all from the scheme as it stands.

However, there would be other consequences - despite the stated intention of concessionary travel arrangements to leave operators “no better nor worse off”, there would almost certainly be an adverse effect on bus services which are already experiencing a long term crisis in use (7). There is no question too that many people do benefit from concessionary travel and these benefits should not be dismissed lightly. It is politically inconceivable that the scheme would be scrapped entirely.

Options for redistributing budget could include providing more direct support to bus services generally; however, as the current scheme is intended as a subsidy for passengers, rather than operators, the fairness of this switch is questionable. Offering free travel to young people (generally, a poorer age cohort than 60-somethings) could assist with job and college travel and encourage a sustained culture of public transport use; but of course that too would be a blunt (and expensive) instrument, like any other age-related eligibility criterion.

My favoured option would be to return to free travel concessions being principally aimed at encouraging local travel. In urban Scotland, this would mean free travel within local cities and surrounding areas while in rural areas, ‘local’ travel still often involves long distances. However, should the scheme pay for expensive long-distance leisure trips that many relatively affluent and mobile pensioners can currently enjoy for free? A study of the distribution of journey lengths funded by concessionary schemes showed that 19% of trips were over 25 miles long (8). The fares for longer bus trips are of course more expensive than for short bus trips; so it would be reasonable to assume that these longer trips make up at least 20% of the concessionary travel budget (perhaps considerably more). My guess is that, even allowing for the need to keep concessions for longer distance ‘local’ travel in rural areas, excluding of long-distance leisure trips from the free scheme might save 10% or more of the current budget; this would in itself provide some £20 million each year which could be used more effectively.

For me, the unique opportunity is to address the long-standing anomaly of disabled people who have the most significant mobility restrictions being excluded from the benefits of concessionary travel entirely. Community transport ‘Section 19’ operations could become eligible for concessionary travel and more ambitiously, a national taxi subsidy scheme for people who can’t use buses and need door-to-door transport could be established. Both of these could be easily achieved at a relatively modest cost.

This is the time not just for tweaks to the current scheme but for fresh and imaginative thinking on how public money can best be used make travel truly inclusive. To do this, we must move away from outdated spending models based on arbitrary age groups and focus more on need.

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-38718556

- http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2016/12/6610/14

- http://www.transport.gov.scot/system/files/documents/tsc-basic-pages/Transport%20Scotland%20agreement%20letter%20to%20CPT.pdf

- http://www.poverty.org.uk/04/index.shtml.

- https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/comms/R107.pdf

- http://www.audit-scotland.gov.uk/docs/central/2010/nr_101007_concessionary_travel.pdf

- http://www.transport.gov.scot/report/SCT01171871341-05.

- https://www.transport.gov.scot/publication/concessionary-travel-customer-feedback-research-year-one-report/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed