The introduction of a Taxicard scheme was not my idea; my then boss Keith Gowenlock proposed the service as part of ‘the multi-modal approach’ to accessible transport that Lothian Regional Council (LRC) was developing. This was supported by the head of the Public Transport Unit David Chambers, and at a political level, by Councillors Ron Muir and then David Begg who chaired the Transport Committee. The Lothian scheme was loosely modelled on the London Taxicard scheme which the GLC had funded for some time along with dial-a-ride services. Interestingly, a taxi subsidy scheme had also run in Edinburgh for a number of years, administered by the rather unfortunately-named Edinburgh Cripple Aid Society (which has since re-branded solely as ‘ECAS’). The ECAS scheme issued “chits’ giving discounted fares to a group of disabled people for use with a contracted local taxi firm, Radiocabs.

Edinburgh District Council had also been the first council outside London to stipulate that all taxis must become wheelchair accessible. Along with this requirement, Edinburgh led the way in training taxi drivers on how to assist passengers using wheelchairs, with mandatory sessions for drivers overseen by the Cab Office, then managed by the police. Unquestionably, not all taxi drivers welcomed these new obligations, but a Taxicard scheme could complement these regulatory measures by encouraging disabled people to use taxis, stimulating customer demand.

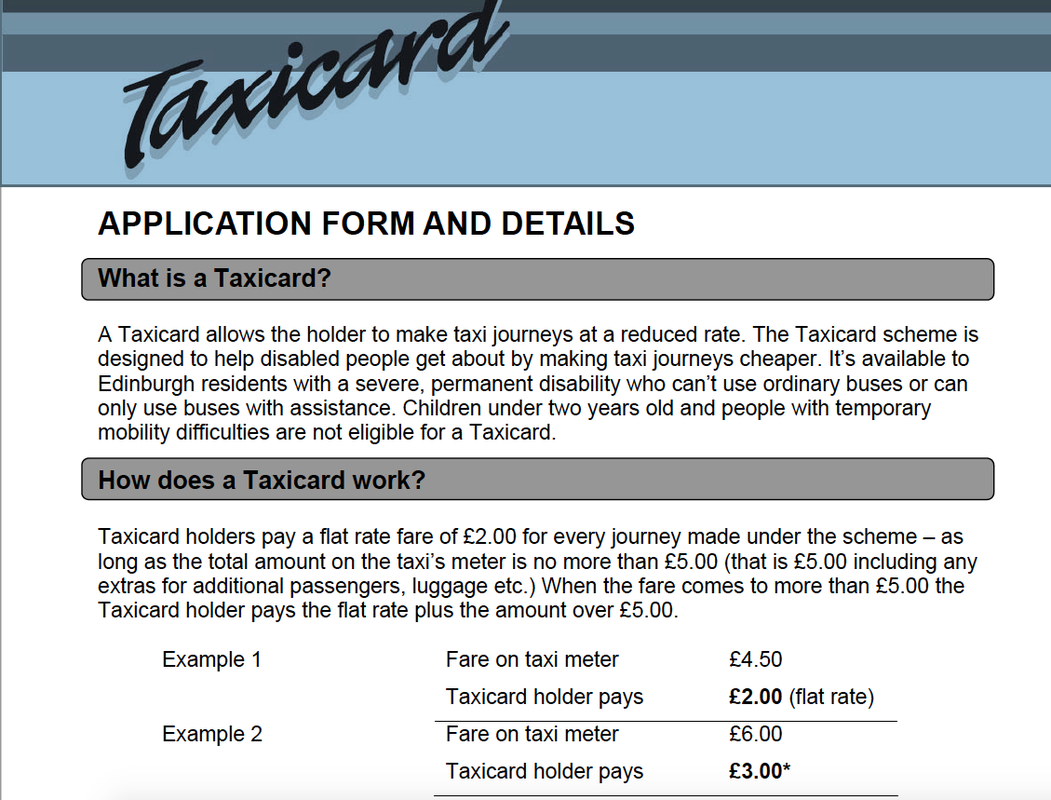

So the Lothian Taxicard scheme was launched in 1992, offering a maximum of 104 single trips a year (this maximum limit echoed the demands of the ‘One Trip a Week’ campaign for dial-a-ride funding which I had led in London a few years earlier). The chief criterion for eligibility for a Taxicard was that the applicant was unable to use buses. Local taxi and private hire companies were invited to participate in the scheme, so that there was usually both a choice of service provider, and of vehicles type. The user had to make a minimum payment of £1.00 and would pay no more until the fare exceeded £5.00; anything above that was payable by the passenger. In 1992, this subsidy of up to £4 per trip paid for a reasonable distance. Triplicate receipt pads were issued to participating companies, with passenger, council and taxi firm each getting a copy. The scheme was launched in West Lothian and then rolled out to the other councils with (from memory) an annual budget of £0.5 million. It is hard not to feel a little nostalgic for a time when a local authority had both the money and the political will to initiate new services like this!

Unsurprisingly, the scheme was immediately popular, with rapidly-developing demand for Taxicards and immensely positive feedback. The number of trips by Taxicard quickly outstripped those by dial-a-ride and Dial-a-Bus, and with a financial ceiling per trip, it represented a cost-effective way of significantly increasing travel options for many disabled people to the council. A Taxicard Users’ Association developed, which became influential as a disability-led group campaigning for accessible transport. The scheme was part of the reason that Lothian Regional Council won the first Equality Award by the European Commission in Scotland in 1995, and several other regional councils introduced similar schemes. However, controlling budgets was always a problem and it was administratively cumbersome, with thousands of trip slips processed monthly to control the 104 limit and to check taxi invoices. Eligibility was largely controlled through requiring that Taxicard applicants did not also hold concessionary travel (bus) permits but eligibility was always prone to ‘grey areas’ given that people do not neatly fall into two boxes - those who can, and those who can’t ‘use conventional buses’. As buses have become more accessible and concepts of disability (including mental health) have changed, eligibility has no doubt become more contested.

The scheme survived local government re-organisation in 1996, with each of the four successor unitary councils in the Lothians maintaining their own Taxicard schemes. However, over the years, the benefits provided have been eroded as senior officials gave the scheme less priority and reduced budgets. The minimum flat rate contribution by the passenger was raised to £2.00 and over time, the remaining £3.00 subsidy went less and less far - literally - due to taxi fare inflation. Perhaps I’m reading more into this than I should, but I’m struck how the scheme logo in Edinburgh today is completely unchanged from 1992! While the scheme continues in the local authorities today, Midlothian closed the scheme to new entrants in 2015.

However, there is no doubt in my mind that the Lothian Taxicard scheme made a huge impact in opening up the possibility of spontaneous travel for many disabled people. It also contributed to making taxi services more disability-friendly and helped raise the bar - in terms of both expectations, and delivery - of inclusive travel in Scotland. These are important legacies

RSS Feed

RSS Feed