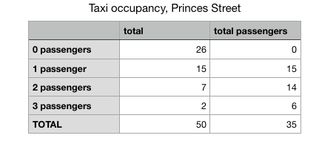

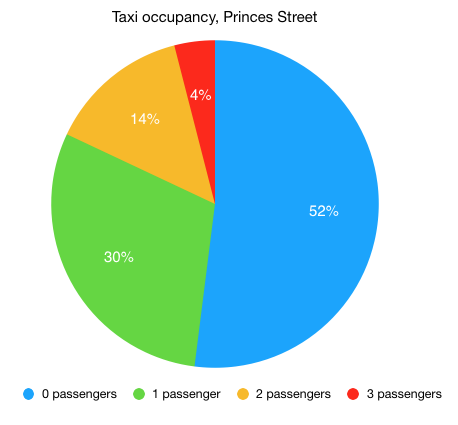

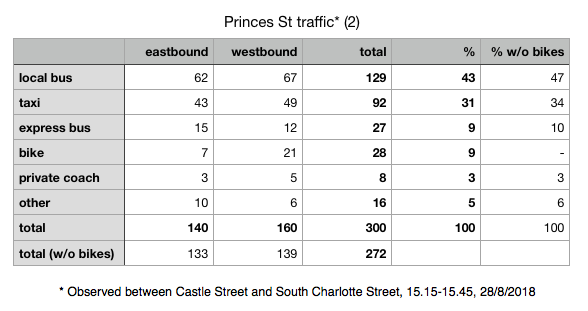

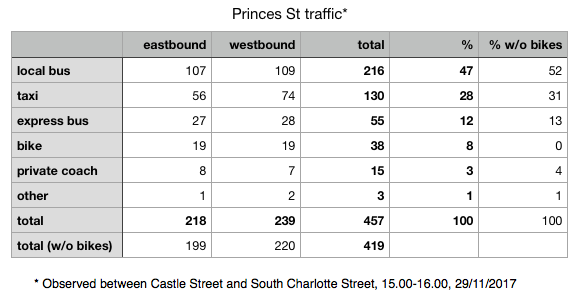

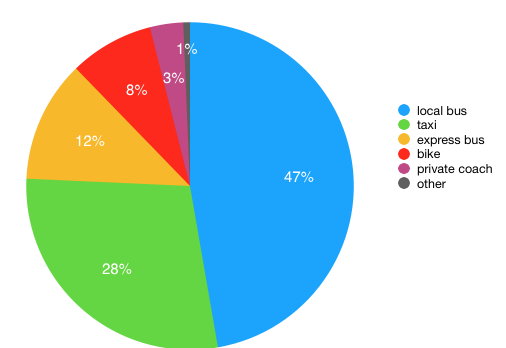

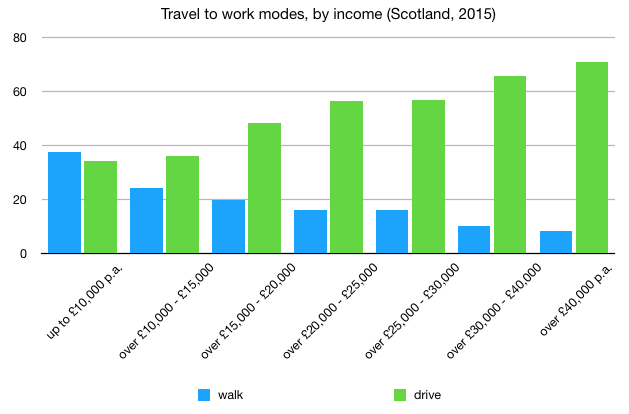

Thousands of taxis use Princes Street each day - my surveys suggested that they could form more more than a quarter of all vehicles on the street. But many taxis carry no passengers at all. I carried out a count of how many passengers occupied 50 taxis in the block between Frederick and Hanover Streets in half an hour on the morning of 2 April. Just over half the taxis passing had no passengers, with the driver either plying for hire, or off duty. Only 9 (18%) carried more than one passenger. The average occupancy of all taxis was 0.7 people (excluding the driver, obviously). More detailed surveys of different parts of the street and at different times are needed to establish better data, but these results raise important questions. Is this an efficient way to move people in the city centre? Is this the best use of the premium space that is Princes Street? Removing taxis would reduce congestion and pollution, speed up buses and make cycling safer.

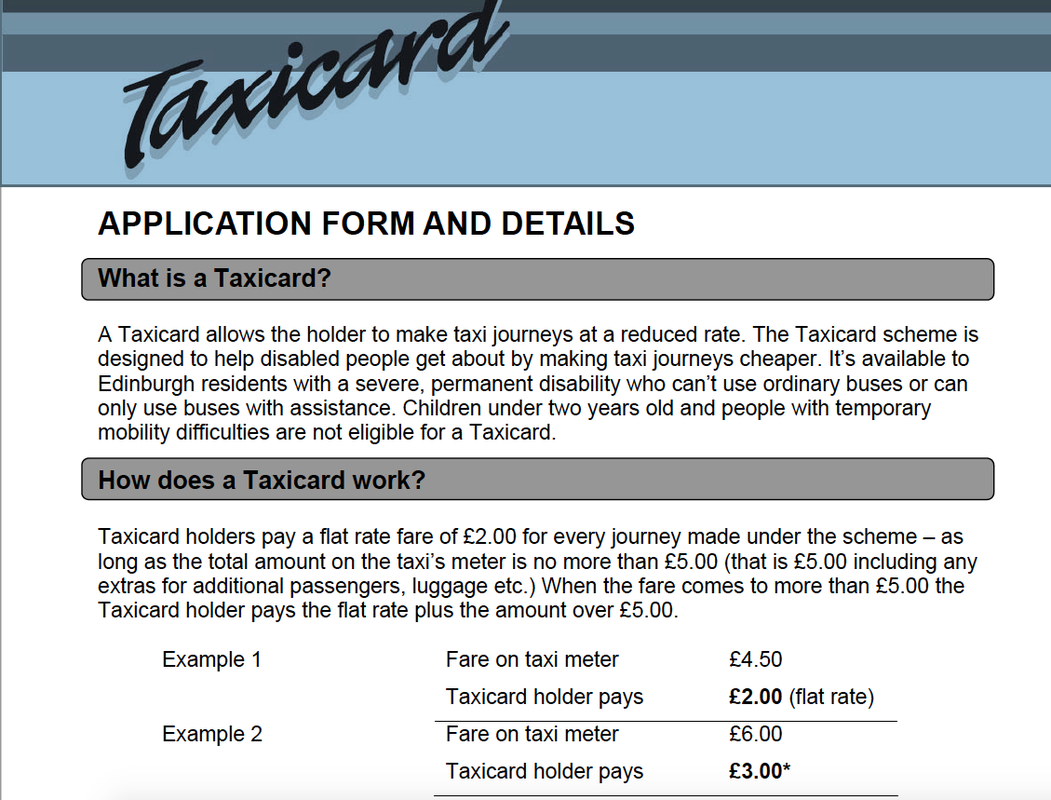

I am a big fan of taxis as an important (and often under-valued) part of the transport mix, especially for disabled people and others who need door-to-door transport. But at the end of the day, taxis aren’t there for the benefit of the taxi trade. There are wider interests to consider and it would be timely to have a renewed discussion about where taxis are, and aren’t, appropriate in a city centre less dominated by traffic.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed