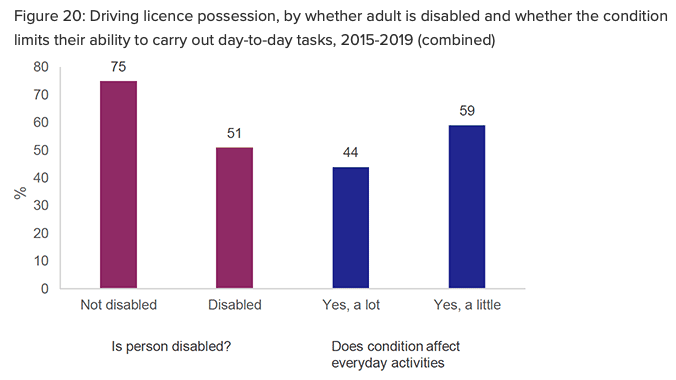

That disabled people use cars less and drive less is beyond dispute. For example, Transport: Disability and Accessibility Statistics for 2020 (1) states that the rate for holding a driving license in England is 60% for disabled people aged 17-64 years compared to 78% for non-disabled people. It also shows that disabled people make fewer trips by car than non-disabled people. This pattern is reinforced by numerous other sources, including Transport Scotland’s ‘Disability and Transport’ 2021 (2) which reports that 51% of disabled people hold a driving licence compared to 75% of non-disabled people (see chart below). Their households are also less likely to have access to a car (52% compared with 77%).

This logic is misplaced for two reasons. Firstly, disabled people who drive are often far more dependent on their cars than non-disabled people. Just in Scotland, more than 200,000 people have a Blue Badge and there are thought to be some 70,000 Motability customers. Alternative modes - public transport and ‘active travel’ - are often not an option, not only because of physical accessibility but for the impact on time, pain management, anxiety, toilet needs and a whole host of other considerations. Door-to-door is a vital consideration for many disabled people, not only for cars but also taxis (which are used approximately twice as much by disabled people as by non-disabled) and community transport. This point is, to be fair, largely recognised by policy makers (including the Transport Scotland 20% reduction team cited above). Witness for example exemptions for Blue Badge holders to a range of restrictions from parking controls to accessing Low Emission Zones.

The second reason why measures to reduce car travel can adversely impact disabled people is that disabled people are often reliant on cars, not to drive them, but as a passenger, and perhaps even more importantly, to assist formal or informal carers. Many disabled people rely on family visits as well as for lifts, and on services coming to their front door. These kind of support networks aren’t helped in any way by Blue Badges and such like, and these impacts seem to me to be often overlooked.

We need to take account of this broader context especially when considering measures like Low Traffic Neighbourhoods which physically restrict cars. Such measures don’t affect all car users equally and far from benefiting disabled people, can have serious unintended negative impacts on disabled people’s mobility and wellbeing. We must surely look to reduce the amount of unnecessary car travel for all kinds of reasons (health, environment, economy) but understanding the potential impacts on disabled people of measures to achieve this at the outset is vital if they are to be fair, and to command the widest possible public support.

(1)https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/972438/transport-disability-and-accessibility-statistics-england-2019-to-2020.pdf

(2)https://www.transport.gov.scot/publication/disability-and-transport-findings-from-the-scottish-household-survey/

(3)https://www.transport.gov.scot/publication/draft-equality-impact-assessment-a-route-map-to-achieve-a-20-per-cent-reduction-in-car-kilometres-by-2030/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed